The temperature reached during composting is primarily the result of microbiological activity, which in turn is governed by moisture content, aeration and substrate (food) availability. Heat builds up in compost because of the insulating properties of the mass, i.e. when the rate of heat gain is greater than heat loss. Small volumes of organic materials (<1–2m3) might not heat up because the heat generated is quickly lost to the atmosphere.

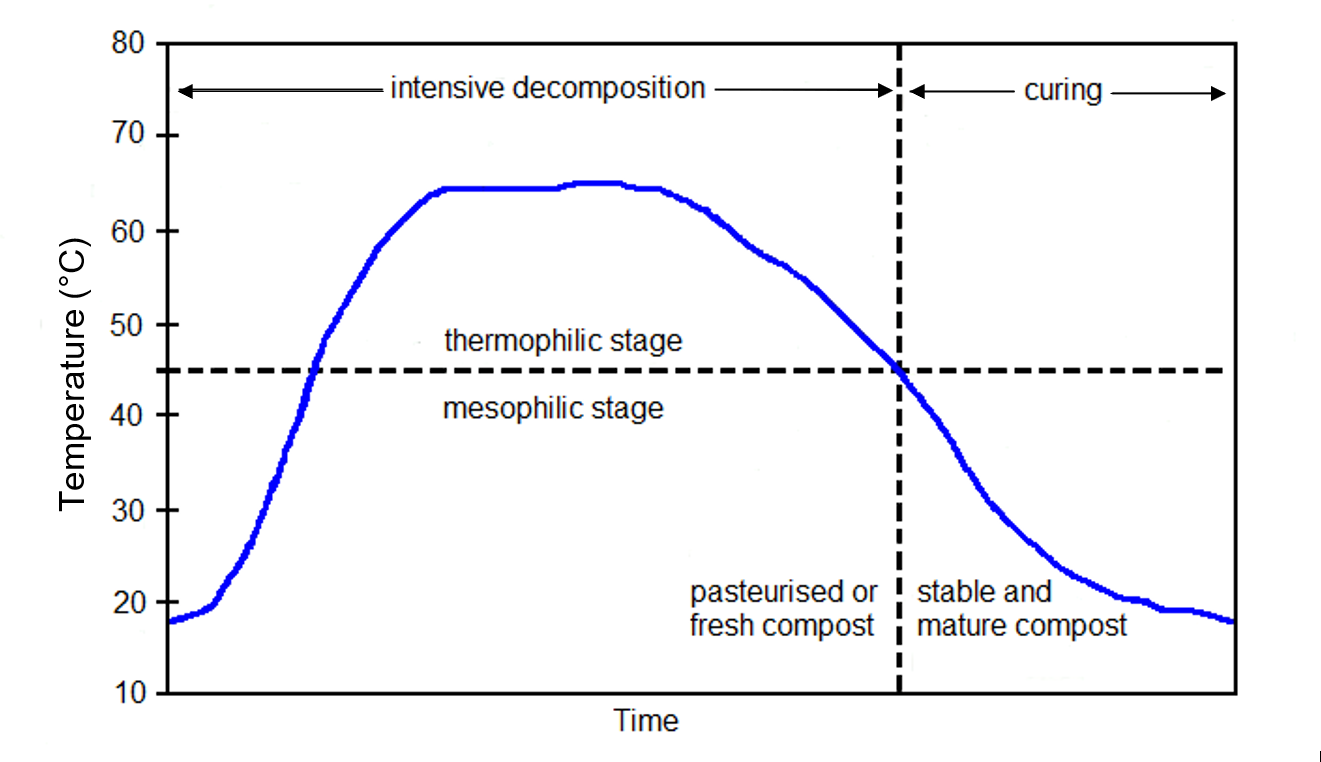

Temperature has a self-limiting effect on microbiological activity and, thus, on the rate of organic matter decomposition. Few microorganisms remain active and survive above 65°C, therefore the composting rate rapidly declines. Thermophilic conditions begin at temperatures above 45°C. The highest rates of decomposition usually occur at 45–55°C mainly because of the activity of thermophilic bacteria and the high speed of biochemical processes in this temperature range.

The different phases of composting are shown in Figure 1. Low temperature (i.e. near ambient) can indicate that the composting process is completed, but keep in mind that temperatures can also fall during composting as a result of other factors, such as limited moisture or air.

Temperature affects organic matter decomposition by directly influencing the make-up of the microbiological population. In a compost pile, a dynamic food-web is at work: there is a succession of organisms that predominate, depending primarily on temperature and the types of food available for consumption. Bacteria, fungi and actinomycetes all play major roles during composting. Some types of invertebrates, such as nematodes, mites, earthworms, snails and slugs, consume organic residues, but they are active at lower temperatures towards the end of the composting process.

Compost feedstock is a complex mix of organic materials ranging from simple sugars and starches to more complex molecules, such as cellulose and lignin. The decomposition of organic matter is a dynamic process because different microorganisms have the capacity to break down compounds of varying complexity and resistance to degradation. Compost microorganisms first consume compounds that are easier to break down than more-resistant compounds (Table 1). Hence, the degradation of sugars, starches and amino acids often marks the initial stages of the composting process. The soft tissue (protein) of poultry mortalities is thus easily degradable in composting, though the larger bones (e.g. beaks) take longer to break down. In addition, layer manure and poultry litter are highly degradable and are therefore excellent additions to any compost mix.

After the easily degradable compounds have decomposed, microbiological activity decreases and temperature falls to below 45°C. Lignin, being more resistant to decomposition, is degraded more slowly, predominantly by fungi growing at these lower temperatures. Materials such as pine sawdust and shavings have high lignin contents and are therefore poorly compostable on their own.

Table 1. Relative susceptibility of organic compounds to decomposition during composting (adapted from Epstein 1997).

| Organic compound | Susceptibility |

|---|---|

| Sugars Starches, glycogen, pectin Fatty acids, lipids, phospholipids Amino acids | Very susceptible |

| Protein Hemicellulose Cellulose | Usually susceptible |

| Lignocellulose Lignin | Resistant |

During the curing or maturation phase, temperature declines further until it becomes identical to the ambient temperature, and compost quality improves significantly. Mature compost is safe to use and is a versatile product for many different applications.